You are here

Italian Cassoni

- A Note on Sources

- A Note on How I've Referenced Stuff

- Intro

- What's so important about cassoni?

- Where do cassoni fit in the wedding?

- A side note on the "Menare a Casa"

- To the Cassoni...

- Phase One

- Phase Two

- Phase Three

- Inlay Chests

- Enter Phase Four....

- Conclusion

- Footnotes

- Image Sources

- Bibliography

A Note on Sources

The Met Museum and the V&A both have quite large collections of cassoni; there are also a large number in private collections. Karen Larsdatter of course also has a page of links to quite a few cassoni, which was useful to me in putting together the original slideshow. In addition, the Burlington Magazine had a few articles from the early 20th century on cassoni - if you have access to JSTOR you should be able to find these, otherwise they have an online index available of articles (although I think you may need to pay for them, or be a member to access them). The Met Museum also has online some brief articles about love and romance etc in Italy during the Renaissance, which are quite useful in terms of contextualising cassoni; the article in the V&A's book "At Home in Renaissance Italy", and Brucia Witthoft's article on marriage and marriage chests in Florence, were also of good use. All of these things are of course listed below in the bibliography. If you want to read from a period source about how to decorate cassoni, I suggest Cennino d'Andrea Cennini's The Craftsman's Handbook "Il Libro dell'Arte", a particularly nice (and cheap) print version of which can be found here, although there are also free online versions available.

A Note on How I've Referenced Stuff

I have footnoted things where the information came from a specific article. Taking a totally non-academic attitude, please assume that anything I haven't referenced came up in the majority of my sources listed above and in the bibliography. Where I'm thinking for myself, there's usually going to be a big clue at the start of the sentence, running along the lines of "I think that..." or "it seems to me like...". When I talk about noticing phases in the development of cassoni style/decoration, these are my own thoughts, and might be quite different (and less accurate) from what those better-educated in the field of art history might think. If you are unsure about anything and would like clarification on it, please do email me at shannon at shannonloveschocolate dot net dot nz and I will get back to you. Unless you're spam.

Intro

Back to top

The traditions and styling associated with Italian marriage chests is quite unique and distinct from what was going on in Northern Europe at the time - right through from the 14th to the 16th century. There are of course style overlaps - especially by the time you get to the 16th century - but I think that for the most part, they really need to be considered separately from Northern European chests.

Terminology-wise we hit a bit of a stumbling block. Not a huge one, but one to pay attention to. A "cassone" in Italian is actually just a chest. It doesn't need to be a wedding chest by default. Witthoft points out that actually, wedding chests, at the time they were being produced, were referred to as "forzieri" (singular "forziere")[1]. However, just about everything you're likely to read on marriage chests is going to refer to them as "cassoni", and "cassoni" are almost always going to be synonymously identified as "marriage chests" - even though, technically, you can just have a plain old cassone that isn't a marriage chest.[2] Although I understand the distinction between the two (and I hope you do as well), just like everybody else I'm going be using the term "cassone" and meaning "marriage chest", or "cassoni" meaning "marriage chests".

And so, onward into the realm of pretty storage....

What's so important about cassoni?

Back to top

Firstly, they're totally cool, which should in itself be enough. But let's back this up with evidence and reasoning, and look a bit at the role they played in marriage ceremonies of the time.

Secondly, they're quite well documented. And that's just awesome. We have surviving records from cassoni makers listing what they made for whom and when, with the amounts paid for them. We also have a number of surviving cassoni that come with information about who they were made for - occasionally, they've been passed down through families. In more instances, they come with sets of arms painted on them, which is an especially-handy identifier when you combine it with the surviving marriage records of the time and voila! you can identify exactly when they were made. If you can also then teem it up with the makers' records, how cool is that?

Thirdly, unlike Northern European chests, they were usually decorated all the way around (Northern European ones tended only to be decorated on the front), because of their different usage and role.

And fourthly, they played an important part in the actual wedding - which leads us neatly on to the next topic....

Where do cassoni fit in the wedding?

Back to top

You'll notice here that I referred to "cassoni" - i.e., the plural of "cassone". "Why?" you might ask. Well, for one very very good reason: cassoni come in pairs. You just don't buy one cassone. You buy a pair, because they're wedding chests, and what do you get at weddings? Monogrammed his and hers towel sets. Or, if you're in Renaissance Italy, you'd get a set of matching his-and-hers chests.

There's a few important bits in an Italian marriage ceremony. Of course there's plenty of different regional variations too. Lots of people have written plenty about it, some of which is listed in the bibliography below[3]. Once the terms were agreed upon, the whole thing could take anywhere from three months to a year. Anyway, to chunk it down briefly for at least Florentine and Venetian marriages:

- Tee up a decent marriage broker to sort out the legal and financial side of things between the parties. Remember to set aside several years for this.

- "Facemmo la giuramento" (making the oath) - get all the blokes on both sides together with a notary. The donora (trosseau part of the dowry, as well as the counter-trousseau from the goorShake hands on it, and sign the legal agreement.

- Spend a few months getting all the necessary stuff organised dowry-wise, with the groom sending the occasional pretty trinket to his bride-to-be

- "Annellamento" (the ring ceremony) - the groom pops a ring on the bride's finger, in the bride's home.

- "Messa del Congiunto" (the joining feast) - feast put on by the bride's father, followed by the consummation of the marriage. At this point in time, we enter options A, B, and C of wedding ceremonies. Option A has the groom consummating the marriage at the bride's father's house, then leaving her there until he's made sure that the dowry comes through. Option B is consummating the wedding at his own house, then packing the bride off home again until he's gotten that dowry payment. Option C is to consummate it at his house (after the "menare a casa") and keep hold of her. There are actually surviving records showing that canny grooms did actually wait (in some cases for four years) to make sure they got every last penny before bringing their spouses home.[4]

- "Menare a casa" (leading to the house) - the wedding procession from the bride's father's house to the groom's house. If you're poor, get a couple of mates and walk your stuff over to the house. If you're wealthy, take with you your entire supportive entourage, a bunch of musicians, a few parade floats, some puppets and other entertainment, and the display of your dowry.

At this point in time (the "menare a casa"), cassoni become important. Whilst originally the entire dowry was put on display - with all the various dresses on their own separate stands - over time, sumptuary laws prohibited such excess, and the dowry was required to be carried in closed chests. So guess what happens? Those chests become the most lavishly decorated items that money can buy - or at least, somewhat cheaper lookalikes of super-expensive ornamentation. Because after all, you've still got to have some way of showing off exactly how wealthy you are. Funnily enough, you then get sumptuary laws limiting the level of decoration and ornamentation of cassoni - with limited effect. After all, the Renaissance is surely what the term "conspicuous consumption" was created for.

Traditionally, it was part of the groom's job to provide the cassoni. This was because he was the one responsible for providing the furnishings for the bedroom. Other items that he provided for this were the lettaio (bed), lettucio (day bed - kind of like a sofa), and the spalliere. These last were painted wall panels, that also came as a pair and went with (as in matched) the cassoni. They've managed to cause a fair amount of dispute among scholars as no-one can agree about how high they were hung on the wall. But more about that later.

So, the groom gets the furnishings for the bedroom, and at the appointed time he has the cassoni sent around to the bride's father's house so that they can be filled with all the linen and clothing and so forth, ready to go. He's also meant to go around and have a wee look at the dowry, to verify that it matches with what he's supposed to be getting. Not doing this (which happened occasionally) was found to be insulting. And, unless you had made a special arrangement for the father of the bride to provide the cassoni (this occasionally happened), not providing any cassoni was also extremely insulting.

A side note on the "Menare a Casa"

Back to top

I'd read how these wedding processions had parade floats and so forth, and while I could sort of imagine it, it really can be quite hard to get an accurate idea of what was being done. I suspect there was definitely a scale in place, depending on just how wealthy you were, that influenced what you did. The full on excess would definitely have been limited to the absolute wealthiest of families. In a moment of serendipity, I came across an image of some floats from the late 15th century wedding parade of Costantio Sforza, nephew of the Duke of Milan, and Camilla of Aragon, natural daughter of the King of Naples. It's part of a book recording the wedding celebrations, and in the Papal Library.

[i]

[i]

Subtle doesn't begin to describe it. The amount of disruption that this must have caused in a town must have been phenomenal - and created a headache for those involved in the infrastructure. You can sort of understand why they might want to impose limits on this sort of thing. In another extraordinary display of excess, from a wedding of the same period, they actually had to knock down houses to make way for the parade.[5]

To the Cassoni...

Back to top

Okay, so in my talk, I gave a little bit of info about the development of styles that I had noticed, and we then went through and looked at the progression. Here, I'm going to discuss the development of the styles whilst looking at the progression, as I think this will work better.

Of course, this really all needs to be considered in terms of what was happening with art of the time, and also what was going on with the decoration of different types of boxes (for example, forzerini - small jewellery boxes - and such). So this is really a fairly preliminary study, yet to be backed up with a full investigation of Everything Else.

Construction-wise, cassoni tend to be made of fairly cheap wood - pine or spruce - then coated over with canvas, gesso, or pastiglia, or any combination of these. I'm not sure how they were actually jointed together; it's something that I haven't had time to look at yet, and it's also made harder by the level of decoration applied to these.

Phase One

Back to top

First up is what I like to think of as the "Early" phase of cassoni decoration. Cassoni were popular from the mid-14th century, and for me this first phase of decorative styling goes from abuot then to about the start of the 15th century. Of course, we have limited surviving examples from this period, so it makes it hard to draw very strong conclusions about it. However, in general, the early cassoni appear to have been a lot more 2D than their descendants will be. They tend also to go for repeating motifs rather than a full-on scenic shot. And they tend to be more definitively box-shaped: less in the way of embellishment of the feet (if there are any) and lid than what we will come across later.

This first example below, dating from the second quarter of the 14th century (1325-1350), displays a simple all-over motif. To me, it looks like the frame of the cassone has been carved, but the inset panel may be pastiglia (embellishment made from applying a thick paste to the surface, and shaping or carving it to decorate) It looks as though the motif is of an eagle, so perhaps it is from someone's device. Or maybe there's an eagle of love that I have yet to learn about?

[ii]

[ii]

My second example, dating from the 1350s, was dated based on the sleeves of the women, which were apparently only in fashion at that particular length for a decade. When I was presenting my slideshow, I introduced as "quite simple and plain really". Gales of laughter ensued. But really, compared to what we're going to see in another century or two, this is a very plain chest. What you've got to realise is that we're talking about the Renaissance. In Italy. More really is more, and "do you think that maybe that's a little too much?" is just not a question that was asked (except maybe in terms of pricing - although I have yet to explore haggling and mercantile practices in any actual depth).

[iii]

[iii]

Anyway, what we're seeing here again is repeating motifs. However, this time they're painted rather than carved. This is one of my all-time favourites - the colours are fantastic, and it's using images that you might also see in, say, 14th century embroidered French purses (what I'm trying to say here, is that it's using a fairly common theme and style for its time). The V&A, where it is now stored, mentions that there are also written descriptions from the time talking about "red and blue girls' chests" which is interesting of itself, as it suggests that this may have been quite a popular style. The themes? Twue Wove and Womance - such a common and generic theme. Yes, that's the Fountain of Love between the couples, and the woman riding the horse is on the Hunt of Love. I don't know about you but I'd be a little bit disturbed by someone chasing me down on horseback and sicking their hunting bird on me.

What you might have noticed in the first image of the chest, is the fact that the interior of the lid is also decorated. This was in fact quite normal, although we'll see an alternative mode of decoration just a wee bit later. I'm not sure whether the decoration extends all the way down the interior, or whether it was just the lid and maybe the top edge that was decorated. It's on my list of things to do to email the V&A and ask them about this, as I'm quite curious to know. This is an example wherein the whole box has been covered in canvas before being painted, and then decorated with a bit of tin leaf for good measure.

Phase Two

Back to top

Moving on now to what I would consider to be the second phase in the developmental style (c.1400-1450), where we continue to see very low-relief surface embellishment, and a preference for pastiglia, gilding, and paintwork - but not necessarily yet fully developed stylistically or thematically.

The next example (c.1410) shows us how many cassoni actually survive: as panels. I was having great issue with a lot of what I was reading, when someone would refer to a panel and say "it's from a cassone". I wondered how on earth they could know it was from a cassone, when what they actually had was a painting on a plank of wood. I think factors such as subject choice and size probably play into it; however, in the example below, it's fairly clear that it came off a chest. Why? Because it's still got the hole for the key in the framework. I've also since discovered that in a couple of instances where people have said "oh yes, this is from a cassone", they do still have the framework around the panel to help identify it as such - they've just edited it out of the image they're showing you.

[iv]

[iv]

It shows a theme that will crop up time and again, and is, funnily enough, well-suited to a marriage chest. That's right, it's the wedding ceremony. L-R: Exchange of rings, procession, wedding feast. With the rather cloying phrase written in the middle, "I give you my heart". Again note what is either low-relief wood carving, or application of pastiglia, on the framework, and the restrained use of gilding over this.

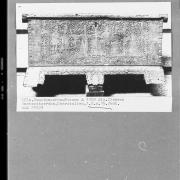

Now we come across a couple of interesting examples where the cassoni have definitely had the images carved directly into the wood. I find these interesting because they're quite different from what you'll find going on in Northern Europe in terms of carving at this time: chests further North, while still in relatively low relief, are carved more deeply than these and with very architecturally-based designs. The trouble with these two chests is that it's a bit hard to work out what they're actually portraying. This is because they would originally have been painted - and unfortunately over time, this painted surface has worn off.

[v]

[v]

Taking a look at this one, it looks as though we have some very tall hats and headdresses going on. It also looks suspiciously like there's a fountain in the middle of the panel - so I think that it's perhaps the ring ceremony, with the lovers standing either side of the Fountain of Love, and family members/general onlookers at the edge on either side.

The second one also has a suspiciously fountain-like object in the centre, but it's harder to tell exactly what the figures around it are doing. It's a celebration of some sort - probably to do with a wedding.... The figures moving around the fountain look as though they may be dancing. But it also looks as though some of the outliers of this group are paying homage to the characters clustered on the right and left of the panel. I really like the way they've added in building walls as part of the background - but then carried on with the scrolling foliage ornamentation with the little putti and deers directly above the central group of people. Because of course, you couldn't just leave that space empty.... What's interesting here also is that, unlike on the previous chest, you can see lines that have been either carved or drawn on, to outline the folds of clothing and details on the fountain and buildings.

[vi]

[vi]

Phase Three

Back to top

Moving on through to about 1425, we now find that we're hitting a bit of an overlap with the second phase. There's still a lot of pastiglia and gilding that likes to carry on until about 1450 - but from about 1425, we begin to see more and more examples of cassoni that have full on painted pictorial scenes as the mode of decoration. There are still a whole lot of nice wedding processions being painted, but also a whole new variety of stories crops up. These are very rarely religious in theme. There's a chunk from popular stories of the time (e.g., the Decameron), but the majority are taken from classical stories and historical occurences.

It's this use of classical themes instead of generic Love and Romance, combined with the use of paint as the major form of decoration, that for me distinguishes this second phase of cassoni.

Theme-wise, it continued to be important to get marriage in there somewhere. So oftentimes, when you're not portraying the elements of a wedding, you'll find stories that show themes of fertility and love, or chastity and love. Petrarch's Six Truimphs crop up from time to time, although with more of an emphasis on Love, Chastity and Death than the others (Fame, Time, Eternity). The wedding procession still showed up, and, as it had obvious allusions to military triumphs, they'd often be paired up with one of these (I mention these again in three paragraphs).

Stories of reconcialiation were also important, as marriages were often contracted to bring two families together. Consequently, with typically Renaissance style and sense of appropriateness, you'll often find chests where one has a beautiful depiction of the rape of the Sabine women, and the other the reconciliation of the Romans and the Sabines.

It was often also important to have some sort of moral tale going on as part of the story. Again, with typical Renaissance flair, you often ended up with some quite tragic stories (think: the death of Eurydice), or stories about the consequences of imprudence and infidelity. Or of course you could go for something subtle like the death of Virginia.

If they were going for real-life stories, classical triumphs were always popular. You've got Alexander the Great, and Julius Caesar - and Scipio Africanus. Or, alternatively, "Scenes from the life of..." were also quite common. Again, covering the famous classical 'greats' - and then some that you perhaps wouldn't expect, such as "Scenes from the life of Seneca" (yes, really). And finally, there's always the fall of famous cities, whether historical or fictional - the fall of Troy, perhaps, or, much closer in time, the Fall of Pisa and Battle of Anghieri (this was actually painted on a cassone about two generations after it happened).

Anyway, looking at some more examples now, we'll kick off with a front panel from around 1420-1425 (workshop of Giovanni Toscani), which is nicely bordering the two phases. It's really neat because it has a bit of gilding and pastiglia happening around the border, but the panel itself is painted, and depicts scenes from the Decameron (apparently the tale of Ginevra, Bernabo, and Ambrogiulo - the first part). To give you an idea of the scale, the entire length of the panel (including the border), is just on 195cm.

[vii]

[vii]

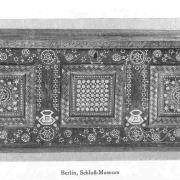

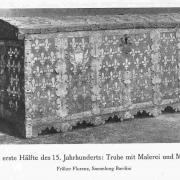

The next image, from the first half of the 15th century, actually reminds me more of the first two examples: the simple repeating motif is reminiscent of the all-over design of the first, while the application of the metal strips, the shape, and the repeating narrow pattern bands at top and bottom along the front are very similar to the second. All of this would almost incline me to date it earlier, except that I assume that whoever has dated it knows more about these things than I do. So therefore, it's interesting to see the survival of this kind of style 50-75 years on, as another is coming into prominence. One more point of note with it is the presence of the two coats of arms on either side of the front panel. This is, as I mentioned earlier, one of the things that's cool about cassoni as it helps us to date them and match them to specific families and workshops.

[viii]

[viii]

An example of a cassone still clearly in the second phase of decoration and embellishment, the next makes pretty full-on use of gilding, over a pastiglia surface. This one's interesting because it shows the other option of displaying devices on cassoni: instead of having his and hers, one on each side, they have gone for all of one (either his or hers) on this chest - presumably its counterpart had the device of the other family.

It's hard to tell whether the cassone above has been carved, or whether pastiglia has been applied. It's interesting to note, because although we have seen this type of lid before, this sort of raised shaping as part of a lid is about to take off in a big way. Again, this one appears to either portray the marriage procession, or perhaps couples dancing. The angels with the shields on either side of the panel are unusual - but again, they're something that's about to become a lot more common, yet in a more 3D way. What's perhaps oddest about this the front panel of this cassone is the fact that it's not completely filled in with stuff. There's actually quite a lot of blank space going on above the figures, which is an unusual compositional choice for a Renaissance Italian artist. This leads me to wonder if perhaps this was originally filled in with more painted images - perhaps scrolling foliage?

The shape of the chest above is more common to travelling chests, and it seems that some cassoni were specially made for couples that travelled a lot. William de Wyke explained that this shape works better structurally for strapping to either side of a horse to transport it. I mostly included this one because it's compositionally weak, but awfully entertaining. You may recall that one of the common themes of cassoni included fertility - and really, what else have fluffy bunnies ever represented?

This leads us nicely on to the two cassoni below (mid 15th century). I mentioned earlier that the insides of cassoni were usually painted as well, and that we'd come across this concept again. Well, here we do. As often as not, the inside of the lids of cassoni were painted with nude men and women - you guessed it, in matching his & hers pairings.... And it actually is as often as not that this occurs: someone has done a count up, and you get this kind of porn on roughly 50% of surviving cassoni. This led me to wonder several things. Firstly, do they let the bride know about this before she opens up her cassoni for the first time? Secondly, was there any actual purpose to this beyond titillation? I mean, were they supposed to be educational? "This is what a woman looks like, naked, and this is what a man looks like, almost naked but with the relevant bits strategically covered". And were they generic, stereotypical images, or were they supposed to be portraits of the couple in question? And how awkward a portrait would that be to sit for?

[xii]

[xii]

One other point to note with the chests above is the use of columns. You might notice that these are now quite raised above the surface of the cassoni, and that the columns on the very corners are actually fully in the round. We're now entering the height of popularity for painted cassoni, but also begin to see the first hints of its impending decline in popularity, as you can begin to see a trend towards more elaborate embellishment of the box itself. From about 1450 through to just beyondn 1500, there's an emphasis on architectural elements being incorporated as part of the overall decoration - and these are often becoming very 3D in nature. The lids tend to be more heavily shaped, and more attention is paid to the styling of the feet (claw feet are especially trendy) or base of the cassoni.

[xiii]

[xiii]

The above (1450-1475) is not a small wee thing, although it may look quite delicate. It's 213cm long, and 97cm high - plenty big enough to store a body (or a whole lot of linens, anyway) in. It depicts the meeting of Solomon and the Queen of Sheba (alliance, anyone?). If you weren't quite sure it was Italian, check out the putti musicians on the end there. You can quite clearly see all those bits that I just mentioned, as well as the addition of little statuettes carved fully in the round.

Now hitting 1471, we reach perhaps the most important set of cassoni. These are spectacularly important, as they are the only surviving pair that are completely intact and still maintain their matching spelliare. They were made for Lorenzo di Matteo Morelli's wedding to Vaggia di Tanai Nerli, although they were actually commissioned a year after the wedding took place (although given the segmented nature of an Italian wedding, it's hard to know which bit was being referred to in this instance). They depict Apollo and Daphne, and the Triumph of Chastity (always remarkable).

There are some video podcasts available online that were made to accompany an exhibition of these cassoni. They can be found here.

[xiv]

[xiv]

When you consider that scholars have been arguing about how high the spelliari were hung over the cassoni, you have to think that it was a bit higher than is shown in the photos, as given the very 3D nature of the lid they would be impossible to open otherwise.

This next one is just a wee bit odd, which is why I wanted to include it. It is a travelling trunk, which explains the shape. It was made for the wedding of Elizabetta Gonzaga of Mantua and Guidobaldo da Montefeltro, Duke of Urbino, in 1488. The decoration is very unusual, and quite different from all previous and future examples that I'm including in this article. As well as the devices of the couple, some of the other emblems include "the flames of love" (such an obvious choice), and the symbol of the Compagna della Calza, an order of knights that Guidobaldo's Daddy belonged to.

Proving that it is of course possible to be out of fashion at any time in history, the above cassoni (1475-1500) regresses to pastiglia and gilding, while the cassone shape itself follows more current trends. You might notice that instead of angels to either side of a panel, or statuettes at each end, there are now instead angel busts supporting the corners of the cassoni. This is the final evolution of the supportive figures at the ends (apparently the official term is, well, "terms"), and will crop up time and again in the sixteenth century. It's hard to know exactly what's supposed to be going on on this cassone, but it looks like to the left hand side, a god and goddess are riding on a chariot drawn by two dragons ridden by some other creatures, while in the middle there are a couple of satyrs up to something, and off to the right a centaur and some more satyrs are sitting with a goat beneath some trees. If anyone has any more theories on what's happening in this panel, I'd love to hear them.

Inlay Chests

Back to top

Hitting 1500, I'd now like to make a slight detour off the beaten track, and take a brief look at some inlay. The Italians are doing some quite remarkable things with inlay by 1500. I don't know whether these qualify as forzieri, or whether they were just ordinary chests (well, as far as this degree of inlay can be termed "ordinary"). They don't seem to really take off as a style in Italy (although inlay as a furniture treatment becomes hugely popular at least in England from about 1590) - maybe because of the phenomenal amount of work involved in producing one. But they're worthy of a brief look in, and just to notice as something that's happening at the same time as a completely different style in cassoni decoration is flourishing.

Both examples below demonstrate a heavy Middle Eastern influence, and were likely to have been made in Venice. Unlike cassoni until now, which as you might recall were mostly pine or spruce, they make use of the most expensive woods available. This in itself will put limits on where they could have been manufactured, as you would have needed to be in a city heavily involved in trade to get access to the materials. Think walnut, rosewood, ivory, and ebony.

Enter Phase Four....

Back to top

As we head into the 16th century now, it's going to become fairly obvious that a new style has taken the place of the painted cassoni. Those little bits of wood carving will now become elaborate, fully carved chests - often carved in very high relief. Funnily enough, that cheap pine isn't going to do the job anymore, and the Italians join the French in their use of walnut. For me, what makes this a distinct fourth phase in cassoni style isn't just the fact that they're now carving instead of painting. It's also the fact that now, alongside the use of classical themes/stories/history, they're also using classical styles: a lot of the layouts of the panels is highly reminiscent of Roman sculpture. Finally, of course, the Renaissance love of all things classical also leads to a significant alteration of the shape of the cassoni, as they begin to more greatly resemble sarcophagi.

Having just said all that stuff about classical themes etcetc, the first example here (late fifteenth-early sixteenth century) is one that totally gets rid of this. It's an interesting piece to note, as the carving is deep and all over. Learning new words, we discover that the curvy roundy flourishy bits are called "rinceaux". It's also totally different in style from anything that's going on in Northern Europe at this time, although it will become popular there later. Unusually, it has a completely flat lid - I wonder if this has perhaps been replaced at some point in time? The other interesting thing to note is that it's gotten rid of flat sides - these are now gently curving out.

[ixx]

[ixx]

The next example reverts to flatter panels, although you might notice that they are still bowing out a little more than previously, and that the carving is really quite deep. With the supporting unicorns, it smacks of allusions to virginity. This cassone is also special because, as it borders the third and fourth phase, it's heavily carved - but it was also originally painted and gilded.

[xx]

[xx]

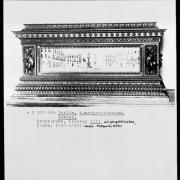

And finally back once more to the world of the completely random, from 1513 comes an example of a cassone decorated with architectural features. Except that it makes use of a painted scene to show someone's cunning mastery of perspective. At least, that's the best theory I've come up with yet. There is in fact one other surviving cassone panel which also features an architectural scene like this, so perhaps there were actually many more of them in existence that just haven't survived. It'll just have to be a bit of a mystery.

[xxi]

[xxi]

Now resuming our normal programming, we get back to a cassone in keeping with the style and themes of the time. Check out the angels supporting those corners - someone wasn't quite up to speed on neck length. Notice also the full-on battle that's going on here. Apparently what's going on here is Hercules versus Antaeus, while the other side depicts the devotion/sacrifice of Marcus Curtius. Perhaps the young lady in question wasn't quite so enamoured of the concept of marriage, and someone here was taking the opportunity to remind her of her duty. They also get the prize for cunning use of heraldry: on one end, the arms of Valvasone of Friuli; on the other, the arms of San Daniele of Friuli, whilst on the lid, the arms of San Daniele impaling Valvasone. In perhaps what is the best piece of descriptive writing about a cassone ever, the V&A says this: "on the basis of the heraldry, the chest appears to have been made for the marriage of Count Beltrami da San Daniele and Vittoria da Valvasone". Astonishing.

[xxii]

[xxii]

Reaching the middle of the sixteenth century, painting has gone out the door and off down the road, and carving has become extremely deep. The carver of this next cassone has gone all out, totally filling in the available space, and especially enjoying those supporting angels (terms). Clearly he's into chests of some sort, anyway. Notice also the bowing shape of the cassone.

A chest from the Medici family, this is the one that perhaps most reminds me of classical sculpture. I also like it because we've got some male terms instead of female ones for once - in this case, some lovely Dacian captives.

Finishing off with one final example from the 1570s, again this cassone is a good example of the full development of the fourth phase on cassoni design. Carved reliefs, again reminiscent of Roman carving, show scenes from Greek myths - the first on the left oddly concerning Apollo, while the remaining three feature scenes from the story of Phaethon. Again, supporting angels are out in large number, not only on the corners of the cassone but also between each panel. And a whole bunch of architectural stuff.

[xxv]

[xxv]

Conclusion

Back to top

As I said at the start, these are my own thoughts on the development of style in cassoni. A number of books have been written on the, however, I have not yet been able to access any of these, so cannot compare my thoughts with what is said there. For me, there is real change and development going on - and real phases of popularity for particular aspects of design, workmanship and themes. They intrigue me also because they are so different to what is happening in Northern European chest making of the time. I think they're an interesting thing to consider as an aspect of Italian marriage that was of great importance for a very long time. They also help to give us an idea of what was considered to be beautiful, and appropriate, and what virtues or aspects of character were considered to be important - after all, they often go in for some quite obscure stories or classical lives to make a point - and for this I think they make an interesting tangible record of part of a culture and society that we might otherwise miss seeing. After all, once they'd played their part in the wedding procession, these were items that were stored in someone's bedroom - that they looked at every day, and that they used everyday to store their linens or underwear. For me, I think the art and furniture that you choose to have in your home and that you choose to look at every day is perhaps of more importance as a marker of a society than those great paintings that you see in public buildings.

Footnotes

Back to top

If anyone can tell me how to get rid of the annoying bullet points while maintaining a list format, I'd greatly appreciate it.

1 Brucia Witthoft, Marriage Rituals and Marriage Chests in Quattrocento Florence, Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 3 No. 5 (1982), p.43. I actually have a few wee issues with Witthoft's article, most notably where she refers to the bride's dowry being on display in an image, when what she's actually referring to is a perfectly normal credenza with its perfectly normal plate display and not a dowry at all. This makes me treat her information with a grain of salt, although it is still an extremely useful article.

2 Well, you could have a plain old cassone, except that the one thing really noticeable about cassoni is that they are never, ever plain.

3 Witthoft, for example, or also the articles on the Met Museum website, or the V&A book.

4 Witthoft has some lovely examples of this kind of thing.

5 Andrea Bayer, Art and Love in the Italian Renaissance, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History article 18/05/2011. Witthoft also refers to one from the same family 30 years earlier that involved knocking down buildings. Maybe it was a family tradition? Or maybe both articles are actually referring to the same wedding records.

6 This image is included as a pdf because I scanned it from an article. If anyone can tell me how to convert the buggers into jpg, I would greatly appreciate it.

Back to top

Those sourced from public collections I have not sought permission to use, as I think that this falls under fair use of these images. Those on private websites I have sought permission to use, and noted this next to the link. Those that I have contacted through the email address provided on their website and had the email address bounce, I have used and noted as such - if anyone reading this has more current contact information for these, please let me know so I can get in touch with them. I have, of course, provided links to the image source in all cases anyway.

iii) The Victoria & Albert Museum

iv) The Victoria & Albert Museum

vii) Art Tattler - used with permission. Workshop of Giovanni Toscani, Cassone, with scenes from Boccaccio’s Decameron (the tale of Ginevra, Bernabò and Ambrogiuolo (part I), c. 1420-25, wood, gesso, tempera and gilding, 82.5 x 195.5 x 68.6 cm (overall), Edinburgh, National Galleries of Scotland.

viii) Medieval Woodworking - the email address provided on this website bounced, so I have been unable to contact them re permission to use this image.

ix) The Victoria & Albert Museum

xi) M. R. R. Italian Renaissance Cassoni The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin, Vol. 18, No. 7 (Jul. 1923), pp. 165-166

xii) Tuscany Arts Files 1 & Tuscany Arts Files 2

xiii) The Victoria & Albert Museum

xiv) Art Tattler - used with permission. Biagio di Antonio and Jacopo del Sellaio, The Morelli Chest and Spalliera,and The Nerli Chest and Spalliera, with scenes from Roman history, 1472, wood, gesso, tempera and gilding, 205.5 x 193 cm (each chest and spalliera), The Courtauld Gallery, London (Samuel Courtauld Trust).

xv) The Victoria & Albert Museum

xvii) Medieval Woodworking - the email address provided on this website bounced, so I have been unable to contact them re permission to use this image.

xxii) The Victoria & Albert Museum

xxiii) The Metropolitan Museum

xxiv) The Victoria & Albert Museum

xxv) The Victoria & Albert Museum

Bibliography

Back to top

Please also refer to all the websites for the images linked to above, as any specific factual information relating to the cassoni came from those websites, as well as little bits of more general information.

Bayer, Andrea, Art and Love in the Italian Renaissance, Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History article, Metropolitan Museum, accessed 18/05/2011.

Bayer, Andrea, Paintings of Love and Marriage in the Italian Renaissance Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History article, Metropolitan Museum, accessed 18/05/2011.

Borenius, Tancred, Unpublished Cassone Panels - I, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 40, No. 227 (Feb. 1922), pp. 70-71 + 74-75

Borenius, Tancred, Unpublished Cassone Panels - III, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 40, No. 229 (Apr. 1922), pp. 189-191

Borenius, Tancred, Unpublished Cassone Panels - IV, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 41, No. 232 (Jul. 1922), pp. 18 + 20-21

Borenius, Tancred, Unpublished Cassone Panels - V, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 41, No. 234 (Sep. 1922), pp. 104-105 + 109

Borenius, Tancred, Unpublished Cassone Panels - VI, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 41, No. 237 (Dec. 1922), pp. 256 + 258-259

Krohn, Deborah L., Nuptial Furnishings in the Italian Renaissance Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History article, Metropolitan Museum, accessed 18/05/2011.

Krohn, Deborah L., Courtship and Betrothal in the Italian Renaissance Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History article, Metropolitan Museum, accessed 18/05/2011.

Matthews-Grieco, Sara F., Marriage and sexuality, Ajmar-Wollheim, Marta, and Dennis, Flora (eds.), At Home in Renaissance Italy (V&A Publications Italy: 2006), pp/ 104-119

Miziolek, Jerzy, The "Odyssey" Cassone Panels from the Lanckoronski Collection: On the Origins of Depicting Homer's Epic in the Art of the Italian Renaissance, Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 27, No. 53 (2006), pp.57-88

M.R.R., Italian Renaissance Cassoni The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin Vol. 18, No. 7 (July 1923), pp. 165-166

Paolini, Claudio, Chests, Ajmar-Wollheim, Marta, and Dennis, Flora (eds.), At Home in Renaissance Italy (V&A Publications Italy: 2006) pp. 120-121

Porter, Laura, Love and Marriage in Renaissance Florence - The Courtauld Wedding Chests, GoLondon accessed 17/05/2011

Schubring, Paul, Cassoni Panels in English Private Collections - I, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 22, No. 117 (Dec 1912) pp. 158-159 + 161-162 + 165

Schubring, Paul, Cassoni Panels in English Private Collections - II, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 22, No. 118 (Jan 1913) pp. 196-197 + 200-203

Schubring, Paul, Cassoni Panels in English Private Collections - III, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 22, No. 120 (Mar 1913) pp. 326-327 + 330-331

Smith, H. Clifford, Italian Furniture, The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs, Vol. 38, No. 214 (Jan 1921), pp. 37-39

Witthoft, Brucia, Marriage Rituals and Marriage Chests in Quattrocento Florence, Artibus et Historiae, Vol. 3, No. 5 (1982), pp. 43-59

- Log in to post comments